AMCA: How India Completed the Design of Made In India Stealth Fighters

The three-story, circular structure is nondescript. It does, however, house a top-secret and high-tech facility. The Aeronautical Development Agency’s headquarters are in Vimanapura, a Bengaluru suburb and an aeronautical hub. This is where India’s finest defence experts are working on a fifth-generation stealth fighter with the support of 250 or so assistants.

The United States has dominated stealth technology thus far. Even Russia and China have not achieved this level of development. The ADA headquarters, unsurprisingly, is protected by multiple layers of security. THE WEEK was invited to Vimanapura for the first time to cover the Advanced Medium Combat Aircraft.

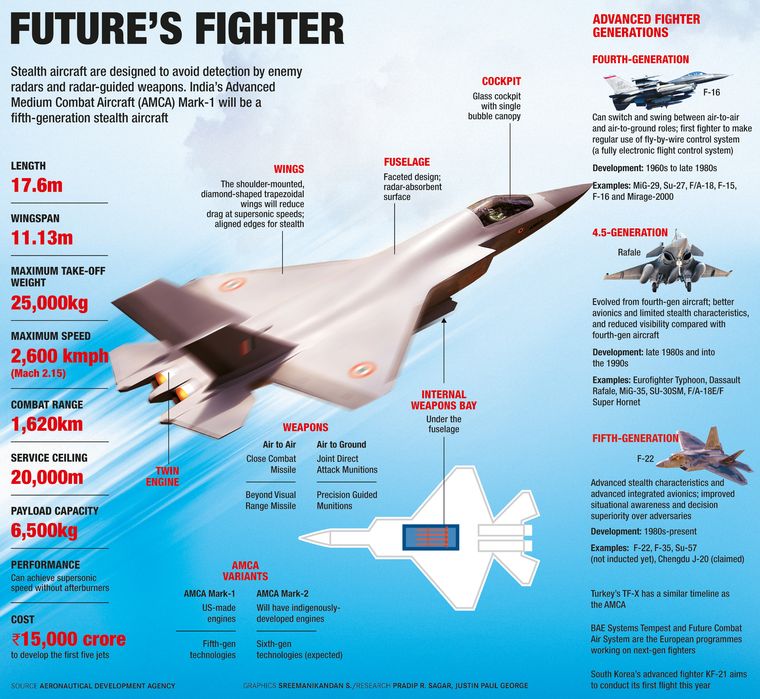

Stealth aircraft are built to avoid being detected by hostile radar or air defence systems. The AMCA is a fifth-generation stealth fighter with a low-observability design. That is, it would be difficult to detect it, and even if it was, the AMCA might ‘disappear’ and approach the target, giving the opponent little time to react.

“Stealth aircraft are necessary in the early stages of conflict to take down the enemy’s air defences,” says Girish S. Deodhare, director general of the ADA. Other fighters, such as the LCA (Light Combat Aircraft), can take over if the air defences are destroyed.”

He claimed that the AMCA’s design was finished. “Now it’s only a matter of building the plane,” he said. A fighter plane includes nearly 15,000 components, all of which have been finalised in terms of design.

The use of a mixture of techniques to limit the reflection or emission of visible light, radar, infrared, radio frequency spectrum, and audio results in stealth technology. “Serpentine air-intake” (which helps lower infrared signature), an interior bay for smart weaponry (rather than wing-mounted weapons), and radar-absorbent material are among the advanced stealth characteristics. It will have AESA (active electronically scanned array) radars that can scan many directions at once, allowing it to achieve supersonic cruise speeds without using afterburners.

The AMCA will be a single-seater twin-engine fighter with a wingspan of 11.13m and a maximum takeoff weight of 25 tonnes. The AMCA Mark-1 will be a fifth-generation fighter, whereas the Mark-2 will almost certainly be a sixth-generation fighter.

The Mark-2 will also have indigenously manufactured engines rather than the US-made engines of the Mark-1 (F414 from GE Aviation). Several countries have expressed interest in partnering on engine development for the Mark-2, according to Deodhare.

The initial development cost of the project is projected to be around Rs15,000 crore. From design through development, experts believe that the F-22 Raptor and F-35 Lightning II stealth aircraft in the United States would have cost roughly Rs1,86,150 crore and Rs1,06,875 crore, respectively.

Lockheed Martin was responsible for the development of both. The F-22, the first fifth-generation fighter, took 20 years to develop (1983–2003), while the F-35 took 16 years (1995-2011). According to current estimates, the first AMCA will be released in 2026.

The ADA organised a small study group to understand the capabilities of a fifth-generation fighter in 2005, when the F-22 was debuted.

Five defence scientists—Ashish Kumar Ghosh, Krishna Rajendra Neeli, M.B. Angadi, A.K. Vinayagam, and Fairoza Naushad—formed the core group to create the stealth fighter in 2009. N.A.K. Browne, the Indian Air Force’s then-deputy head, gave them the IAF’s operational requirements. The ADA’s confidence in attempting the design of a stealth aircraft stemmed from their expertise designing the LCA Tejas.

The project director is Ghosh, also known as “Mr AMCA Man.” The group director, Neeli, communicates with the ministry of defence as well as other stakeholders. Vinayagam is in charge of system engineering, Angadi of configuration (providing the plane its shape and placing systems and equipment within), and Fairoza of avionics.

The F-22 was the only fifth-generation stealth fighter in service when the ADA’s effort began in earnest in 2009. It was extremely manoeuvrable and could cruise at supersonic speeds (at Mach 1.8) without using afterburners. “A feasibility study was begun under my supervision with a budget of 090 crore, including everything from technology to capabilities and appearance,” Ghosh stated. He stated that the team has been talking with IAF personnel to understand the requirements since the beginning.

He went on to say that the LCA programme had taught the ADA that technology development had to begin at the beginning. “So, even while the feasibility study was going on, we started creating the technology,” he explained.

The AMCA team’s original concept was for an all-weather, multi-role fighter capable of aerial combat, ground attacks, enemy air defence suppression, and electronic warfare. After four years, the first practical configuration was developed in 2013, and the IAF approved it.

However, following the success of the BrahMos project, a joint venture with Russia was formed to create a fifth-generation stealth fighter (an India-Russia JV). Following many points of contention, the IAF withdrew from the initiative in 2018.

The IAF, for example, desired the ability to modify the new fighter without Russian assistance. Russia refused to disclose the computer source codes that would allow India to accomplish this. Over the two fifth-generation fighter programmes, the defence ministry was likewise tugged in two directions. All of factors caused delays in the AMCA project, which the IAF eventually decided to focus on.

With the establishment of the National Flight Test Centre in 1996, IAF pilots began to participate in aircraft design. The test pilots, on the other hand, were just providing comments on the aircraft’s performance in the air. The ground crew’s feedback was lacking.

This meant that crucial factors such as readiness and maintenance were overlooked during the design process. The LCA project was finally delayed as a result of this. To address this issue, the AMCA project developed a Project Monitoring Team (PMT) to oversee all elements. The PMT is now made up of 25 IAF personnel and is led by an air marshal.

The PMT attends all ADA meetings and expedites any IAF headquarters clearances that are required. Previously, the ADA had to write to the defence ministry and wait months for IAF approval. All clearances are now completed in two days. “User (IAF) participation is tremendous nowadays,” Deodhare added. “

“Both parties (the IAF and the ADA) are convinced of what can be accomplished physically and technologically.”

The Russians used to say that creating stealth technology for combat jets needs a cooperative effort from two to three nations during the doomed joint venture with the United States. Ghosh and his team, on the other hand, were able to complete the task on their own.

He claimed that developing stealth technology in India had previously been regarded as near-impossible. “Developing the stealth features, such as its shape, paint coating, and radar-absorbent substance,” he stated. “Each and every substance that makes the aeroplane stealth has been finalised, but it took a long time.”

Ghosh noted that stealth qualities and excellent manoeuvrability were prioritised in the AMCA project. The importance of this balancing is demonstrated by the Sukhoi Su-57, Russia’s fifth-generation stealth aircraft. It has yet to be inducted because the Russian military is unhappy with its stealth design, which is more concerned with manoeuvrability.

The US, on the other hand, appears to have a very clear strategy. It also employs the Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit in addition to the two fighters—the F-22 and F-35 (a stealth, strategic heavy bomber, with a wingspan wider than a football field).

Balancing manoeuvrability and low-observability, according to Ghosh, is a difficult task. He used the Lockheed Martin F-117 Nighthawk as an example of the US’s first stealth aircraft.

The F-117 made its first flight in 1981 and went on to prove its operational worth throughout the Gulf War (1990-1991) and subsequent Balkan conflicts. It was built to drop bombs, not for aerial combat, according to Ghosh. “The F-117 had very little manoeuvrability; it couldn’t dodge a missile attack,” he explained. “If it was discovered by the enemy, it was a sitting duck.”

As a result, the US decided that stealth alone was insufficient for the F-22 aircraft, opting instead for a mix of manoeuvrability and stealth. However, the fighter grew so expensive that it could no longer be purchased in significant numbers. The US trimmed down to 173 F-22s from an earlier plan of more than 700.

“They realised that too much performance combined with stealth was unaffordable,” Ghosh explained. “As a result, the F-35 was designed with stealth and manoeuvrability in mind.”

The IAF has determined that only seven AMCA squadrons are required (including the Mark-2). Because of the stealth features, the AMCA will be more expensive than other fighters. Following a meagre Rs90 million allocation for the feasibility study in 2009, the government granted an additional Rs447 crore for design in 2018. To begin manufacturing, the cabinet committee for security (CCS) must first approve it.

The budget is substantially higher than the LCA programme, and the first aircraft will not be built for at least four years after the CCS approval. The paperwork was already in the cabinet secretariat, according to Neeli, and the CCS approval “should be coming any day now.”

The ADA has set a 10-year timeline for building the first five prototypes and conducting flight tests. Each of the five prototypes will cost around Rs900 crore. However, the cost is likely to drop dramatically later in the manufacturing process. Prototypes always cost more, according to defence scientists, because they also test vehicles. However, because the AMCA is mostly indigenous, it would be less expensive than importing.

The basic aircraft might be 50% to 60% less expensive (excluding the cost of weaponry, maintenance, and upgrades). The total cost of ownership will be reduced by 70%.

Aside from the engines, the ejection seats for the Mark-1 are also imported. Sensors, avionics, and flight control systems are all made in the United States. That means that almost 70% of the aeroplanes are made in the United States. Scientists are unwilling to increase the indigenous content since it is not commercially viable. The indigenous content will increase to 90% once the Mark-2 engines are developed.

For the IAF, the AMCA programme is crucial. The world’s fourth-largest air force is dealing with a dwindling combat fleet; it now has 32 squadrons instead of the sanctioned 42.

A pleased Neeli describes the AMCA’s capabilities to the IAF, stating that the fighter will have a top speed of roughly 2,600kmph (Mach 2.15) and a combat range of 1,620 kilometres. It will be armed with a 23mm gun and 14 hard points to carry 6,500kg of armaments. The fuel capacity is also 6,500kg, although the LCA only has 2,400kg.

The aircraft is meant to be lethal in both air-to-air and air-to-ground operations. Brahmos-NG (next generation) air-to-ground missiles, Astra air-to-air missiles, anti-tank missiles, Rudram anti-radiation missiles, laser-guided bombs, and precision munitions will all be installed aboard the AMCA.

The fighter’s “most advanced” features include avionics for pilot communication and sensors, radars, and infrared search-and-tracking capabilities, according to Fairoza.

Fairoza, who is 45 years old, is the team’s youngest member. In 2005, the mother of two became a member of the ADA, the same year the AMCA study group was created. She stated, “Avionics must match the criteria of stealth aircraft.” “We were given the challenge of developing long-range radars with long-range sensors.” Extended detecting sensors (early warning system) and network-centric warfare capability (which will improve pilot coordination) will also be included in the aircraft.

She went on to say that increased situational awareness was another important component of the AMCA.

“Multi-spectral sensors are distributed throughout the airframe, allowing the pilot to have a 360-degree sight without having to manoeuvre the fighter,” Fairoza explained.

This enables “First Look, First Kill,” in which the AMCA pilot detects and destroys the target without the enemy being aware of the threat. Pilots will be able to use a 3D audio warning system and voice-activated orders in the cockpit, which will reduce their workload and allow them to focus more on missions.

The most essential feature of the avionics, however, is the “electronic pilot.” A fighter platform traditionally requires two pilots. One is a pilot who flies and the other is a mission pilot (who directs the flying pilot). “This jet will only have a single cockpit with an electronic pilot,” Fairoza stated. “Without ground support, AMCA can carry out a deep strike.”

Even the most modern fighter jets, such as the Dassault Rafale, require the assistance of another plane or ground personnel.” According to her, the F-35 was the only platform with equivalent capabilities. She did say, though, that she wasn’t sure about the Su-57 or the Chengdu J-20 from China (China claims it is a fifth-generation stealth fighter).

With only 60 scientists, the ADA was established in 1984 as the nodal body for the LCA initiative. Then India had to start all over again. But, with Tejas, it has joined a select group of countries that have developed 4.5-generation supersonic multirole fighters in-house. The LCA project’s delays taught India a lot of good lessons.

As a result, the ministry of defence established a committee in 2019 led by former DRDO chief V.K. Saraswat to develop an AMCA execution methodology.

The process of aircraft manufacturing, which was designed by the ADA and manufactured by HAL, was seen to need to modify and incorporate more parties. The Saraswat committee suggested developing a special purpose vehicle (SPV) with private industry participation to build the AMCA after a year of debate.

The ADA will form the SPV with HAL and private players after the cabinet allows manufacture. The majority of manufacturing is projected to be controlled by private companies. The ADA has already begun conversations with three private companies about responsibility distribution.

One thing is certain, regardless of how the job is distributed. The indigenous stealth fighter developed by India will be more than the sum of its parts and will be cost-effective.

Facebook Comments