At 6 p.m., the head of the Indian Space Research Organisation (Isro), S. Somanath, knew that his organization had done it. He got up from his seat at ISRO Telemetry Tracking and Command Network (ISTRAC) in the Peenya industrial area of Bengaluru, smiled at the worried people around him, and nodded his head as if to tell himself the mission was a success.

Two minutes later, there were loud cheers and applause coming from the operations center, where he and his team were watching Chandrayaan-3’s lander land on the moon’s surface. A few minutes later, Somanath grabbed a microphone and said five words that made the cheers and clapping even louder.

“India is going to the moon!”

Up until then, there was a lot of stress in the big room. The landing process was planned, but a lot of things could go wrong, like they did four years ago when Chandrayaan-2, the mission that came before Chandrayaan-3, had its lander crash onto the moon’s surface. The team got up, brushed themselves off, and went back to work. And, as Somanath said in an interview before the start, it made sure to have plans for plans for plans.

They weren’t the only ones. A whole country held its breath for 18 minutes, which is how long the landing process took. Earlier in the day, people prayed in churches and mosques all over the country, and schoolchildren talked about space and their goals as if nothing else mattered. Since the US landed on the moon in 1969, a whole country hasn’t been as excited about a possible space breakthrough as India was on Wednesday.

Over 60 million people watched a recreation of the landing on the website of the space agency, and many more watched the same feed on TV and news sites. Prime Minister Narendra Modi joined the viewing party at Isro from the Brics Summit in Johannesburg. He waved the Indian flag in response to Somanath’s statement.

“It’s a great gift to see something so important happen…It’s just the beginning for India. We now have to prove our success with trips to the sun and Venus, among other places,” he said.

Later, during a phone call with the head of Isro, Modi said, “Your name, Somanath, means “lord of the moon,” and today you helped India put its flag on the moon. Your family and every Indian will be proud of you.”

That’s true. People brought flowers and boxes of candy and met outside the center. Others danced. Some people cheered. Still others looked up, almost as if they were trying to picture the lander, which was called Vikram, in their thoughts.

And it was clear that everyone at the space agency was moved. The mission’s associate project director, K Kalpana, said that the team had pretty much lived and breathed Chandrayaan-3 since the last trip. Not far from her, but outside the center, Madan Adarsh, a cleaner at ISTRAC, proudly waved the Indian tricolor and said that Wednesday’s landing made him feel like he had done something good for himself.

Other scientists gave V and thumbs-up signs, and Isro’s women engineers, who worked in near-obscurity for years but have been getting more attention in recent years, walked around, hugged each other, and posed for the cameras. Kalpana summed it up with tears in her eyes.

“This is the happiest time of my life, and I’m sure many of us feel the same way today.” Every mistake is a chance to learn something, and we didn’t give up after our last one. Instead, we learned from it and got better.”

Somanath seemed happy to let his team have their moment in the spotlight and did most of the talking himself. When he spoke, he gave a lot of praise to everyone who had worked at the space agency before him. And he made it clear that this was just the start.

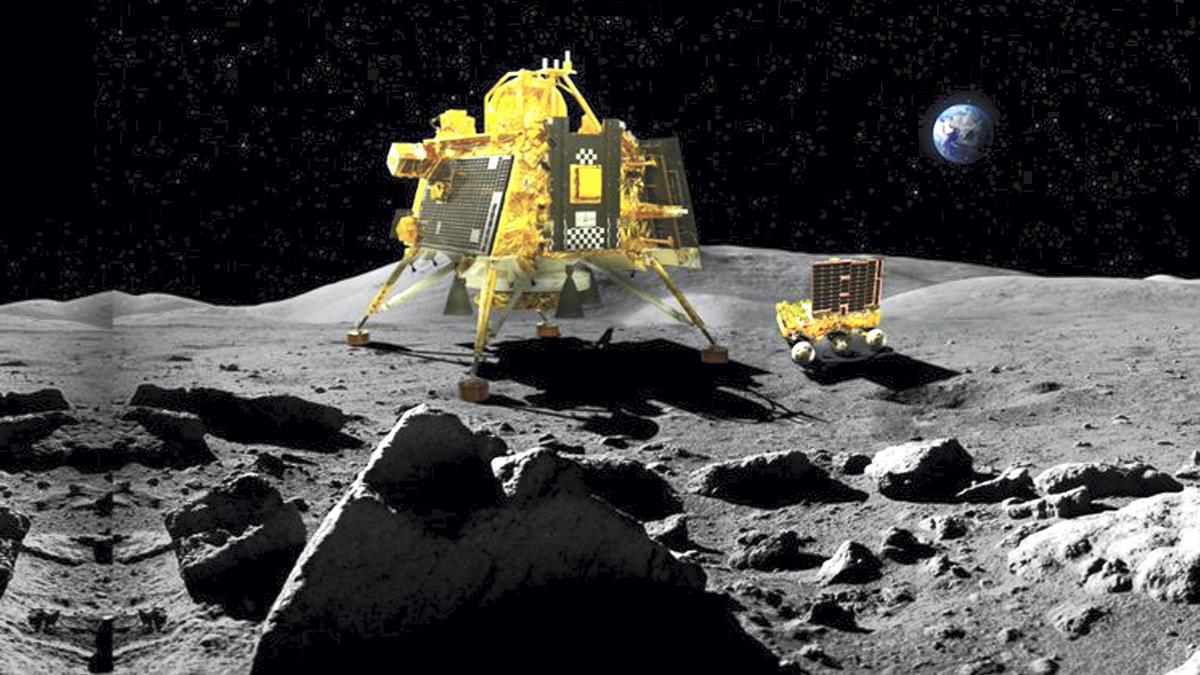

The project’s head, P. Veeramuthuvel, said that if it worked, scientists and engineers at the agency would be able to “sleep peacefully” in four years.

He was using a figure of speech. Even though the party went on until late, so did work. After almost four hours, the rover Pragyan rolled out of the lander. The mission had moved on to the next step.